Simple Thread is a digital product agency with a focus in the electric power industry. The power and electric utility industry is absolutely fascinating in its scale and complexity and we love sharing all of the interesting things we have learned. The topics may vary from facts about the grid, to green energy, energy sustainability, basic electrical engineering, the future of the grid, and everything in between. If you’d like to hear more, keep checking back!

The power grid is the largest, most complex, and most important machine ever constructed. It is the network that enables everything we have in modern society, and yet we are scarcely aware of it until it stops working. It is quite literally the platform that our lives are built on. The United States power grid alone is of a scale that is hard to fathom (these are rough numbers around 2023):

With its millions of interconnected parts, the power grid is mind-bogglingly complex, and yet in the United States we’ve managed to turn it into a mostly reliable system with a few notable exceptions. But that reliability didn’t come about by accident. It came from many many decades of intense engineering, hard learned lessons, and like it or not, government regulation.

Early Days

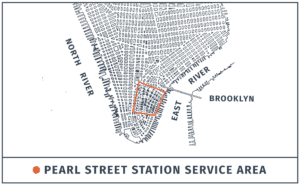

In the early days of electric power production, the equipment that needed electricity had to be at most a few thousand feet from the generator producing it. But it was clear from even the earliest days when the first power plant in the U.S. was built, the Pearl Street Station in New York City, that centralized production of electricity would be the real future of the electricity industry.

But as electric production ramped up, more and more independent power companies arrived on the scene. Virtually all of these early electric companies were vertically integrated, building all of the infrastructure needed to get power from their plant to their customers. These companies usually had a single plant, and served power to a few hundred or few thousand customers in a very small area.

Massive Consolidation

As more and more of these companies appeared, it quickly became apparent that there were economies of scale to be achieved. Building and maintaining electrical infrastructure is expensive, and so as with any industry faced with high capital outlays, consolidation began.

Within the power industry though, the benefits of consolidation weren’t just financial. In addition to allowing them to save money due to reduced infrastructure costs, power companies quickly realized that they could more efficiently use their power plants by networking them together.

For example, if one power company had a hydroelectric power plant, and another had a coal power plant, the coal power plant could provide supplemental power when the river that fed the hydroelectric power plant was low. And the hydroelectric plant could provide cheaper power when the river was high. Or if one power plant had to be taken offline for maintenance, power from other plants could pick up the slack. This enabled a level of reliability that hadn’t previously been achievable.

The benefits of cost savings and reliability led to larger power companies buying up smaller power companies and in some cases even forming agreements with competing power companies to provide supplemental power or power in emergency situations.

Transition to Utility Power

At this time, most industrial electric customers were still producing their own electricity, and felt that “rented power”, as it was called at the time, was too unreliable. But as the demand for electricity within the industrial sector grew, so did the size and reliability of grids, which began to produce electricity at a cost that the manufacturers couldn’t match. The “utility scale” power plants were much more efficient, and were located at sources of power like coal mines or rivers.

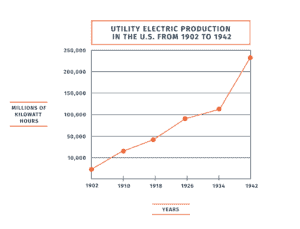

The shift towards “rented power” was so quick, and demand grew so fast, that the fledgling power industry couldn’t keep up. Utility electric production increased over 70x between 1902 and 1942, but still wasn’t enough to meet demand. Leading into World War I power shortages were becoming more common and were affecting wartime production. The federal government began to push for power companies to interconnect in order to better utilize existing power plants.

Power plants that weren’t connected tended to run at much lower utilization rates, as they could only sell as much power as they could get customers in their immediate area. Coming out of World War I larger and larger grids started forming, with organizations like the Interconnected Systems Group being formed by multiple power companies spanning multiple states. The Interconnected Systems Group eventually went on to form the largest synchronized grid in the world at the time.

The Feds Get In the Game

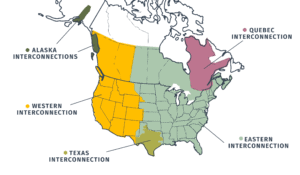

On the eve of World War II the federal government started mandating interconnections between utilities in order to avoid power supply issues if wartime manufacturing should increase. This process continued after World War II, leading up to the mid-1960’s where most of the continental United States was covered by two major grids. In the late 60’s, there was a brief eight year period where the eastern and western grids were actually connected, but this was eventually abandoned due to technical challenges.

These two grids, or “interconnections” as we call them, are actually independent synchronous electrical grids that are internally connected and synchronized, but have only limited connections between them (these connections are high voltage DC connections, which allows the grids to function separately so they don’t have to be synchronized). This allows for power to flow relatively freely, for example, within an interconnection, but not between two different interconnections.

And Then There Were Two

Today, we call those two primary grids within the United States the Eastern Interconnection and the Western Interconnection. These interconnections now span most of Canada and parts of Mexico. There are also three smaller interconnections within the US and Canada: the Texas Interconnection, the Quebec interconnection, and the Alaska interconnection. While they aren’t generally considered part of the North American grid, there are also the Sistema Interconectado Nacional (SIN) of Mexico and the Central American Electrical Interconnection System (SIEPAC).

The Texas interconnection exists for primarily political reasons, as it grew largely separate from the Eastern and Western interconnections and was never absorbed into either out of a desire for Texas to keep its own grid out of the purview of the federal government. Because the Texas interconnection doesn’t cross state lines, it isn’t subject to most federal regulations.

The Modern Grid

The geographical scope of the major interconnections hasn’t really changed since the 1960s, but the grid of today carries almost 3 times the electricity, and the electricity we consume costs us only a third as much in inflation adjusted dollars. We are consuming several times more energy on a per capita basis now, even though we have made huge strides in the energy efficiency of our appliances and other devices.

This is about to change though. The coming wave of electrification of numerous sectors is going to reverse the declining trend of U.S. energy consumption that has been going on for the last 15 years. Some estimates say that in order to achieve our current electrification goals, we would need to double or even triple our grid’s capacity by 2035, which would cost trillions and would be an undertaking that would make the project to build the U.S. highway system seem tiny by comparison.

And while our grid is already one of the largest and most complex machines ever created, it needs to get even bigger. If we want to shift to more renewable energy, then we need the ability to move that energy from places in the country where it is prevalent (solar in the southwest), to parts of the country where it isn’t (northeast). Right now we don’t have this ability, but if we are going to make this shift, we need to figure it out.

Summary

Having knowledge of the history of the power grid probably isn’t at the top of most peoples todo lists. But if more people were aware of what the grid is, how it came to be, and how critical it is to our energy future then we would be able to much more effectively lobby for the changes that will be needed to secure our accelerating demand for electricity.

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.

One objection I keep hearing to our efforts to transition to a low carbon infrastructure is that our electrical grid can’t support the scale and speed of increase needed for a timely transition. Is there historical data about the growth of our present electrical grid that would inform discussion of this issue?

The biggest hurdle to grid expansion seems to be who is going to pay for it. Everyone wants the other guy to cough up the money. It’s not without justification, Transmission line construction is Uber expensive, and the legal battles drag on for years. Once they are built, no one wants to pay the toll that’s needed to pay for this new highway. We have a long way to go.