At the end of the year two years ago, I was trying to remember what I’d done that year and got frustrated that my memory wasn’t great. I could remember the big highlights, and there was photographic evidence of some things to help jog my memory, but tons of little things slipped through the cracks. If my memory was that bad recalling the previous 365 days, I couldn’t imagine how little I’d remember years later.

So I started journaling, and it’s been pretty great! Journaling sets aside a brief moment for self-reflection that I wasn’t doing before. I also find it also helps me feel like time isn’t passing quite so fast.

While most people journal with a physical journal, I knew that at the end of the day I’d be too tired to physically write out everything I wanted to write. I’d get lazy and skip writing things down just so I wouldn’t have to physically write. So I started journaling electronically on my laptop. Not only is typing things out faster and less of a physical pain, you also get full text search and tagging!

Getting Started

When I set up my journal, I wanted to pick a technology that would be around for years. Journaling on the latest app wasn’t something I was interested in. I could imagine anything out there trying to make a profit will inevitably get bought out by private equity, sell my journal entries to train AI, and promptly announce it’s shutting down with an email from the CEO titled, “Our Incredible Journey.”

I chose to write my journal entries in a format called Markdown, and use a “static site generator” called Eleventy that turns the Markdown files into web pages. The creator of Eleventy shares my same sort of mindset of thinking of the web in terms of decades rather than months, so that’s one of the reasons I picked it. But, even if some day I can’t get Eleventy running on my computer, all of the journal entries are simple text files. (I’m banking on some nerd out there making sure computers can always read text files.)

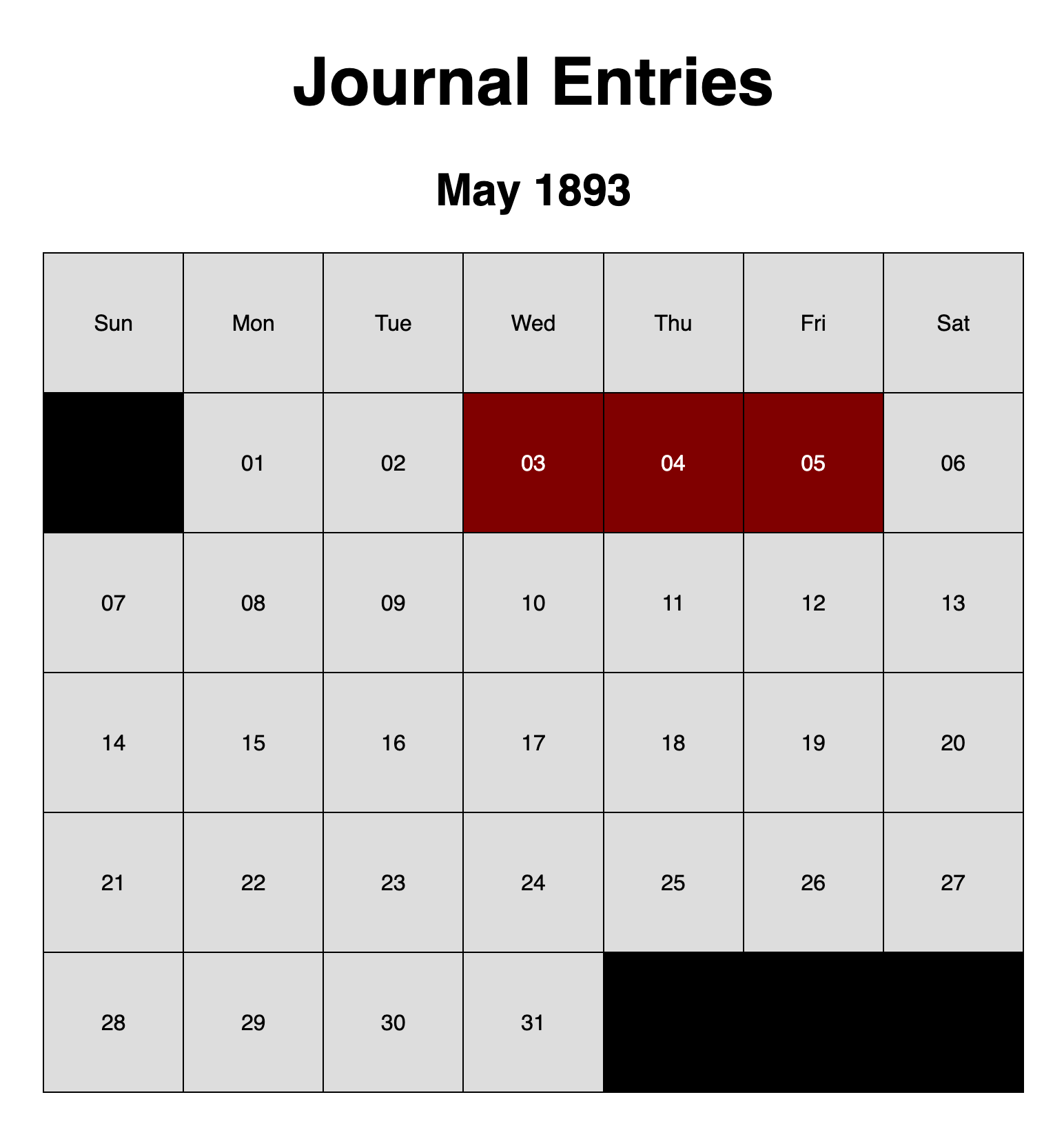

My vision for my journal was to be able to click around a calendar that showed my entries, navigate between to the previous and following entries while reading an entry, add tags to entries, and click the tags to see a list of entries that shared that same tag.

This tutorial assumes some basic knowledge of the command line to get working. Here’s a handy page for how to get to your terminal. And here’s a handy page for how to install Node.

I’m working on a Mac, so everything related to navigating the command line will be for Macs.

When you open Terminal for the first time you’ll be in your home directory. I like putting all of my projects in my Documents folder. So I’ll navigate to Documents by typing in the “change directory” command and pressing enter:

cd DocumentsThen I’ll create a project folder called “journal” by running the “make directory” command:

mkdir journalThen I’ll change directory again, this time into our newly created journal folder:

cd journalNext we’ll create a package.json file by running:

npm init -yWe’ll also want to use ESM instead of CommonJS for our files. So we’ll run:

npm pkg set type="module"This essentially changes the way we import and export code between files. ESM is a newer format that’s also a JavaScript standard, and since we’re thinking in terms of decades, we want to go with standards.

Now we’ll want to install Eleventy:

npm install @11ty/eleventyThis will download all of the files needed for Eleventy and save it to your dependencies in the package.json file we created.

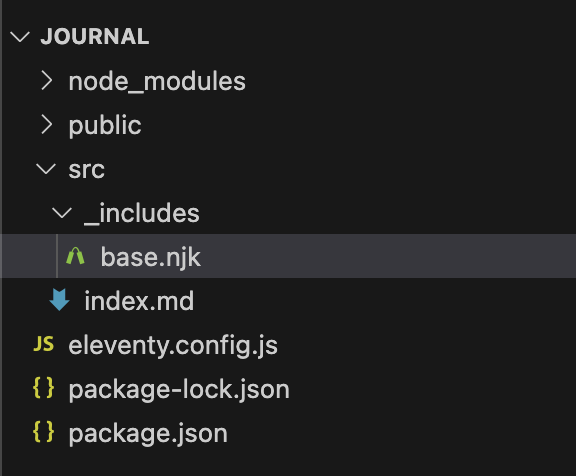

At this point you’ll probably want to go open up your journal project folder in a code editor. You’ll want to create a new file called “eleventy.config.js” and add to it:

export default async function(eleventyConfig) {

return {

markdownTemplateEngine: "njk",

htmlTemplateEngine: "njk",

dir: {

input: "src",

output: "public",

}

};

};This will set the template engine for our Markdown and HTML files to use Nunjucks. (This is just my personal preference, if you want to use a different templating language you can, but you’re on your own figuring out what the equivalent Nunjucks templating code is in the language you pick!)

We also set the input directory to a folder named `src` and the output directory to a folder named `public`.

In our journal folder, create a new folder called `src` and inside of that create a new file called `index.md`.

Inside of your `index.md` file type and save the file:

# JournalBack in your Terminal, you can run:

npx @11ty/eleventy --serveWhich will start up a web server and transform your markdown file into a web page. When you visit http://localhost:8080/ in your web browser, you should see “Journal” in big, bold letters.

Setting Up the Structure

Starting the Server

Before we continue, we’ll want to add a better way of starting and stopping the server. We can add a script to our `package.json` file that’s a little easier to type.

In `package.json` there should be a scripts section that looks like:

"scripts": {

"test": "echo "Error: no test specified" && exit 1"

},Remove the “test” script and replace it with:

"scripts": {

"dev": "npx @11ty/eleventy --serve",

"build": "npx @11ty/eleventy"

},Then in our Terminal, to start our server we just need to run:

npm run devLayouts

Next, we’re going to want to create a layout. We’ll have a few layouts eventually, but our first will be our base layout. This is the HTML structure that the rest of the web page will fit into.

Layouts need to be in a folder called `_includes` that lives inside of the input directory, which we called `src`.

So create a new folder inside our `src` folder called `_includes`. Inside of the `_includes` folder, create a new file called `base.njk`. (.njk is the Nunjucks file extension)

Inside of `base.njk` we’ll add the following code:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>{{ title }}</title>

</head>

<body>

<header>

<h1>{{ title }}</h1>

</header>

<main>

{{ content }}

</main>

</body>

</html>Notice how it’s all HTML, except we’re using Nunjuck’s double curly brackets syntax to put content from variables inside of our web page. If a variable called `title` exists, then we’re going to use it for the title of our web page that will show on the browser tab, and also display it as a heading at the top of all of our pages.

We can pass this variable into our layout from “front matter.” Let’s actually use our new layout for our `index.md` page and pass it a title.

In our `.index.md` file, let’s replace the contents with:

---

title: Journal Entries

layout: base.njk

---

Hello!The key-value pairs between the triple dashes is our “front matter.” The `layout` key is special, and denotes that we want this page to be wrapped in the layout we specify. The `title` is an arbitrary key that we made up, and it’s passed down into the layout. This is what’s between our double curly brackets in our title and header.

Everything below the front matter section gets put into a `content` variable.

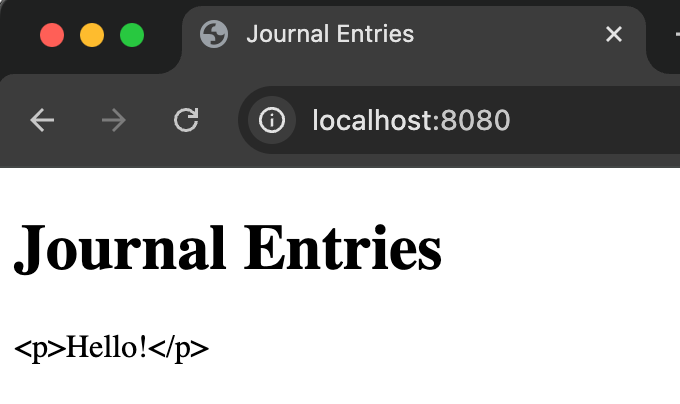

If we take a look at our page now, you can see our page’s title is “Journal Entries”, and there’s a header on the page that says “Journal Entries”, which come from our `title` variable. But our “Hello!” text is wrapped in a `<p>` tag that isn’t actually rendering a paragraph!

In our layout you can see that we’re populating `content` in our `<main>` tag. By default HTML is going to be “escaped” and turned into regular text that doesn’t actually render HTML elements. This is for our safety, but since we wrote “Hello!”, we know that it’s safe!

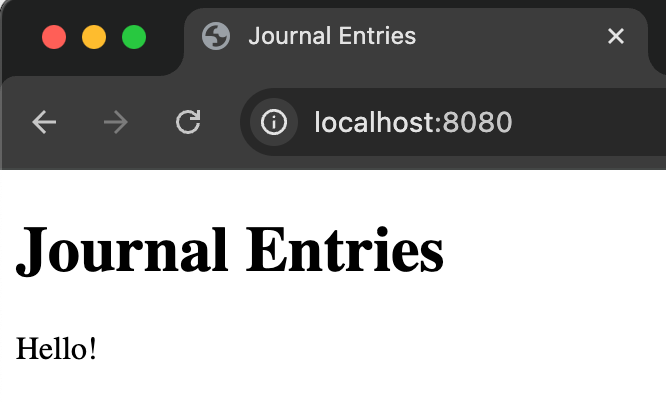

We can use a Nunjucks filter called `safe` to prevent the HTML from being escaped. In our `base.njk` layout file, we’ll add `| safe`. The `|` pipe character says, I want to run some filters, and then `safe` is the name of the filter we want to run.

Our `base.njk` file should now look like:

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>{{ title }}</title>

</head>

<body>

<header>

<h1>{{ title }}</h1>

</header>

<main>

{{ content | safe }}

</main>

</body>

</html>And our page should look like:

Journal Layout

Now that we have our base layout, we now need to create a layout for our journal entries that we’ll nest inside of our base layout.

In our `_includes` folder, create another layout called `journal.njk` and populate it with the following code:

---

layout: base.njk

---

<article>{{ content | safe }}</article>Next we’ll create another folder in our `src` directory where all of our journal entries will live. We’ll call it `journal`.

Before we start adding entries, we’ll create a “data directory” file called `journal.json` inside of our `journal` folder. This will contain:

{

"layout": "journal",

"permalink": "/{{ title | slugify }}/",

"tags": "entries"

}Every page inside of our `journal` folder will get those key value pairs set as front matter automatically. So they’ll all use `journal.njk` for the layout, the permalink for the pages will be the `title` variable that we’ll set when we create a journal entry, and they’ll all have a “tag” of `entries`. This will put all of the files in this `journal` folder into a collection called `entries`. (We’ll come back to this later.)

I like to group my entries in a folder designating the year, then a folder for the month, then the day is the name of the journal entry file itself. If I was creating an entry for May 3rd, 1893 my file structure would look like `1893` > `05` > `03.md`.

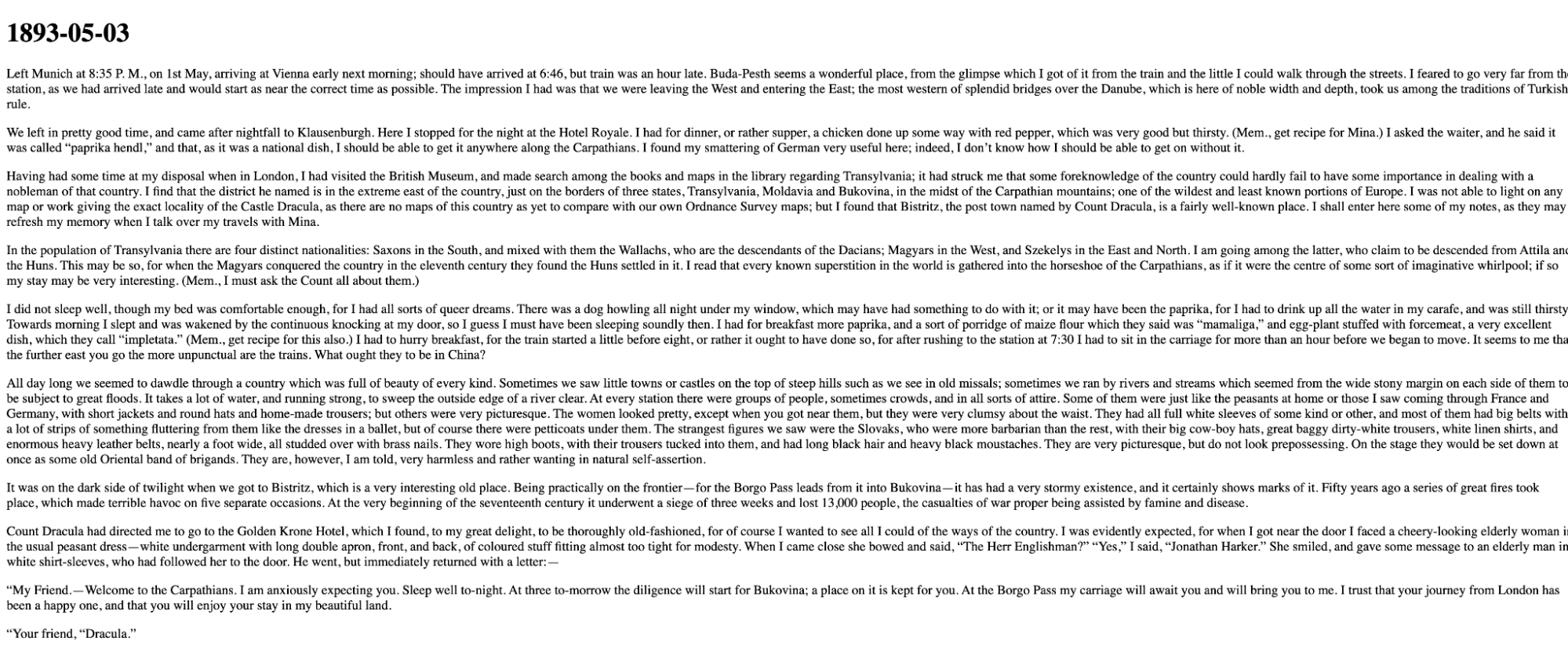

Create these folders and file and populate `03.md` with the following:

---

title: "1893-05-03"

date: 1893-05-03

tags:

- Dreams

- Food

---

Left Munich at 8:35 P. M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late. Buda-Pesth seems a wonderful place, from the glimpse which I got of it from the train and the little I could walk through the streets. I feared to go very far from the station, as we had arrived late and would start as near the correct time as possible. The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most western of splendid bridges over the Danube, which is here of noble width and depth, took us among the traditions of Turkish rule.

We left in pretty good time, and came after nightfall to Klausenburgh. Here I stopped for the night at the Hotel Royale. I had for dinner, or rather supper, a chicken done up some way with red pepper, which was very good but thirsty. (Mem., get recipe for Mina.) I asked the waiter, and he said it was called “paprika hendl,” and that, as it was a national dish, I should be able to get it anywhere along the Carpathians. I found my smattering of German very useful here; indeed, I don’t know how I should be able to get on without it.

Having had some time at my disposal when in London, I had visited the British Museum, and made search among the books and maps in the library regarding Transylvania; it had struck me that some foreknowledge of the country could hardly fail to have some importance in dealing with a nobleman of that country. I find that the district he named is in the extreme east of the country, just on the borders of three states, Transylvania, Moldavia and Bukovina, in the midst of the Carpathian mountains; one of the wildest and least known portions of Europe. I was not able to light on any map or work giving the exact locality of the Castle Dracula, as there are no maps of this country as yet to compare with our own Ordnance Survey maps; but I found that Bistritz, the post town named by Count Dracula, is a fairly well-known place. I shall enter here some of my notes, as they may refresh my memory when I talk over my travels with Mina.

In the population of Transylvania there are four distinct nationalities: Saxons in the South, and mixed with them the Wallachs, who are the descendants of the Dacians; Magyars in the West, and Szekelys in the East and North. I am going among the latter, who claim to be descended from Attila and the Huns. This may be so, for when the Magyars conquered the country in the eleventh century they found the Huns settled in it. I read that every known superstition in the world is gathered into the horseshoe of the Carpathians, as if it were the centre of some sort of imaginative whirlpool; if so my stay may be very interesting. (Mem., I must ask the Count all about them.)

I did not sleep well, though my bed was comfortable enough, for I had all sorts of queer dreams. There was a dog howling all night under my window, which may have had something to do with it; or it may have been the paprika, for I had to drink up all the water in my carafe, and was still thirsty. Towards morning I slept and was wakened by the continuous knocking at my door, so I guess I must have been sleeping soundly then. I had for breakfast more paprika, and a sort of porridge of maize flour which they said was “mamaliga,” and egg-plant stuffed with forcemeat, a very excellent dish, which they call “impletata.” (Mem., get recipe for this also.) I had to hurry breakfast, for the train started a little before eight, or rather it ought to have done so, for after rushing to the station at 7:30 I had to sit in the carriage for more than an hour before we began to move. It seems to me that the further east you go the more unpunctual are the trains. What ought they to be in China?

All day long we seemed to dawdle through a country which was full of beauty of every kind. Sometimes we saw little towns or castles on the top of steep hills such as we see in old missals; sometimes we ran by rivers and streams which seemed from the wide stony margin on each side of them to be subject to great floods. It takes a lot of water, and running strong, to sweep the outside edge of a river clear. At every station there were groups of people, sometimes crowds, and in all sorts of attire. Some of them were just like the peasants at home or those I saw coming through France and Germany, with short jackets and round hats and home-made trousers; but others were very picturesque. The women looked pretty, except when you got near them, but they were very clumsy about the waist. They had all full white sleeves of some kind or other, and most of them had big belts with a lot of strips of something fluttering from them like the dresses in a ballet, but of course there were petticoats under them. The strangest figures we saw were the Slovaks, who were more barbarian than the rest, with their big cow-boy hats, great baggy dirty-white trousers, white linen shirts, and enormous heavy leather belts, nearly a foot wide, all studded over with brass nails. They wore high boots, with their trousers tucked into them, and had long black hair and heavy black moustaches. They are very picturesque, but do not look prepossessing. On the stage they would be set down at once as some old Oriental band of brigands. They are, however, I am told, very harmless and rather wanting in natural self-assertion.

It was on the dark side of twilight when we got to Bistritz, which is a very interesting old place. Being practically on the frontier—for the Borgo Pass leads from it into Bukovina—it has had a very stormy existence, and it certainly shows marks of it. Fifty years ago a series of great fires took place, which made terrible havoc on five separate occasions. At the very beginning of the seventeenth century it underwent a siege of three weeks and lost 13,000 people, the casualties of war proper being assisted by famine and disease.

Count Dracula had directed me to go to the Golden Krone Hotel, which I found, to my great delight, to be thoroughly old-fashioned, for of course I wanted to see all I could of the ways of the country. I was evidently expected, for when I got near the door I faced a cheery-looking elderly woman in the usual peasant dress—white undergarment with long double apron, front, and back, of coloured stuff fitting almost too tight for modesty. When I came close she bowed and said, “The Herr Englishman?” “Yes,” I said, “Jonathan Harker.” She smiled, and gave some message to an elderly man in white shirt-sleeves, who had followed her to the door. He went, but immediately returned with a letter:—

“My Friend.—Welcome to the Carpathians. I am anxiously expecting you. Sleep well to-night. At three to-morrow the diligence will start for Bukovina; a place on it is kept for you. At the Borgo Pass my carriage will await you and will bring you to me. I trust that your journey from London has been a happy one, and that you will enjoy your stay in my beautiful land.

“Your friend,

“Dracula.”In our front matter, the `title` will show in our title and in a header due to our `base.njk` layout, like we’ve already seen. It also is used to create the URL we’ll visit to see our blog post, which we saw with the `permalink` key in our `journal.json` file. We also add additional tags to our post with the `tags` key. We can have multiple tags by using the `-` syntax, in this case “Dreams” and “Food.”

Make sure your server is running, (if it’s not run `npm run dev` in your Terminal) and you can see your journal entry in your browser by visiting http://localhost:8080/1893-05-03/.

Let’s add a couple more for May 4th 1893 and May 5th 1893. For `04.md`:

---

title: "1893-05-04"

date: 1893-05-04

tags:

- Crucifix

---

I found that my landlord had got a letter from the Count, directing him to secure the best place on the coach for me; but on making inquiries as to details he seemed somewhat reticent, and pretended that he could not understand my German. This could not be true, because up to then he had understood it perfectly; at least, he answered my questions exactly as if he did. He and his wife, the old lady who had received me, looked at each other in a frightened sort of way. He mumbled out that the money had been sent in a letter, and that was all he knew. When I asked him if he knew Count Dracula, and could tell me anything of his castle, both he and his wife crossed themselves, and, saying that they knew nothing at all, simply refused to speak further. It was so near the time of starting that I had no time to ask any one else, for it was all very mysterious and not by any means comforting.

Just before I was leaving, the old lady came up to my room and said in a very hysterical way:

“Must you go? Oh! young Herr, must you go?” She was in such an excited state that she seemed to have lost her grip of what German she knew, and mixed it all up with some other language which I did not know at all. I was just able to follow her by asking many questions. When I told her that I must go at once, and that I was engaged on important business, she asked again:

“Do you know what day it is?” I answered that it was the fourth of May. She shook her head as she said again:

“Oh, yes! I know that! I know that, but do you know what day it is?” On my saying that I did not understand, she went on:

“It is the eve of St. George’s Day. Do you not know that to-night, when the clock strikes midnight, all the evil things in the world will have full sway? Do you know where you are going, and what you are going to?” She was in such evident distress that I tried to comfort her, but without effect. Finally she went down on her knees and implored me not to go; at least to wait a day or two before starting. It was all very ridiculous but I did not feel comfortable. However, there was business to be done, and I could allow nothing to interfere with it. I therefore tried to raise her up, and said, as gravely as I could, that I thanked her, but my duty was imperative, and that I must go. She then rose and dried her eyes, and taking a crucifix from her neck offered it to me. I did not know what to do, for, as an English Churchman, I have been taught to regard such things as in some measure idolatrous, and yet it seemed so ungracious to refuse an old lady meaning so well and in such a state of mind. She saw, I suppose, the doubt in my face, for she put the rosary round my neck, and said, “For your mother’s sake,” and went out of the room. I am writing up this part of the diary whilst I am waiting for the coach, which is, of course, late; and the crucifix is still round my neck. Whether it is the old lady’s fear, or the many ghostly traditions of this place, or the crucifix itself, I do not know, but I am not feeling nearly as easy in my mind as usual. If this book should ever reach Mina before I do, let it bring my good-bye. Here comes the coach!And `05.md`:

---

title: "1893-05-05"

date: 1893-05-05

tags:

- Food

---

The grey of the morning has passed, and the sun is high over the distant horizon, which seems jagged, whether with trees or hills I know not, for it is so far off that big things and little are mixed. I am not sleepy, and, as I am not to be called till I awake, naturally I write till sleep comes. There are many odd things to put down, and, lest who reads them may fancy that I dined too well before I left Bistritz, let me put down my dinner exactly. I dined on what they called “robber steak”—bits of bacon, onion, and beef, seasoned with red pepper, and strung on sticks and roasted over the fire, in the simple style of the London cat’s meat! The wine was Golden Mediasch, which produces a queer sting on the tongue, which is, however, not disagreeable. I had only a couple of glasses of this, and nothing else.

When I got on the coach the driver had not taken his seat, and I saw him talking with the landlady. They were evidently talking of me, for every now and then they looked at me, and some of the people who were sitting on the bench outside the door—which they call by a name meaning “word-bearer”—came and listened, and then looked at me, most of them pityingly. I could hear a lot of words often repeated, queer words, for there were many nationalities in the crowd; so I quietly got my polyglot dictionary from my bag and looked them out. I must say they were not cheering to me, for amongst them were “Ordog”—Satan, “pokol”—hell, “stregoica”—witch, “vrolok” and “vlkoslak”—both of which mean the same thing, one being Slovak and the other Servian for something that is either were-wolf or vampire. (Mem., I must ask the Count about these superstitions)

When we started, the crowd round the inn door, which had by this time swelled to a considerable size, all made the sign of the cross and pointed two fingers towards me. With some difficulty I got a fellow-passenger to tell me what they meant; he would not answer at first, but on learning that I was English, he explained that it was a charm or guard against the evil eye. This was not very pleasant for me, just starting for an unknown place to meet an unknown man; but every one seemed so kind-hearted, and so sorrowful, and so sympathetic that I could not but be touched. I shall never forget the last glimpse which I had of the inn-yard and its crowd of picturesque figures, all crossing themselves, as they stood round the wide archway, with its background of rich foliage of oleander and orange trees in green tubs clustered in the centre of the yard. Then our driver, whose wide linen drawers covered the whole front of the box-seat—“gotza” they call them—cracked his big whip over his four small horses, which ran abreast, and we set off on our journey.

...Adding Styles

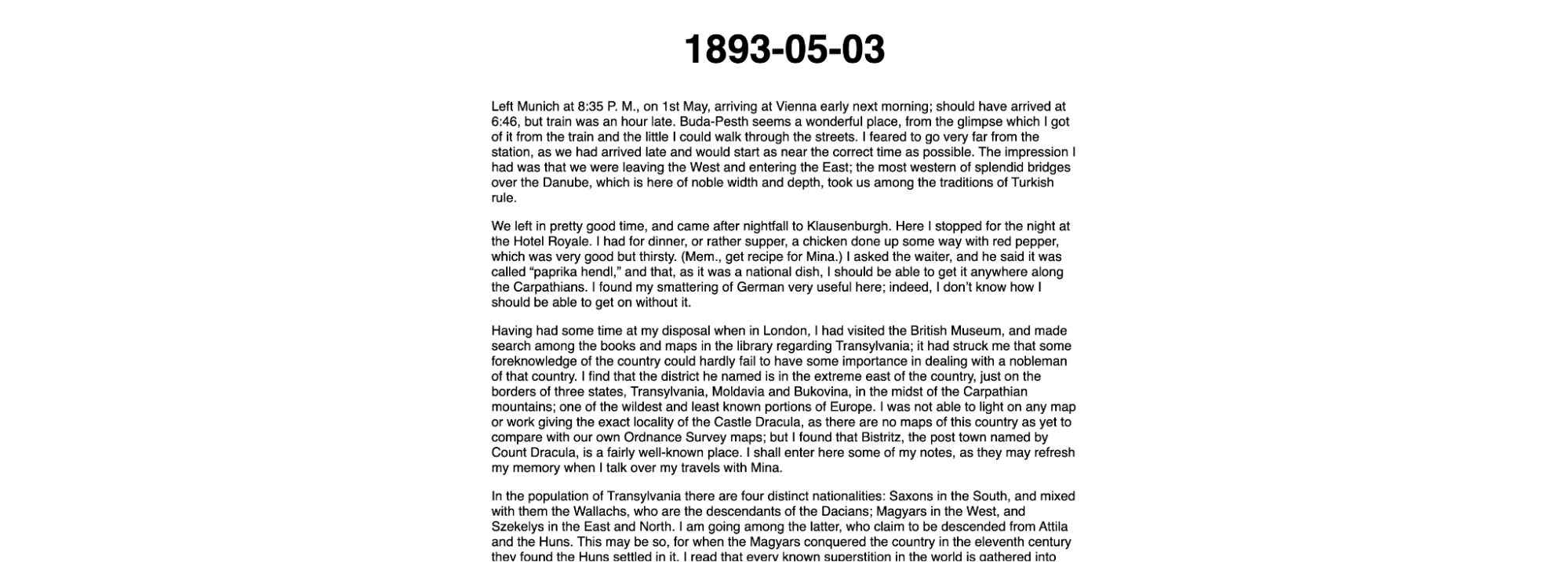

The text on our page stretches all the way across the page which is not very comfortable to read.

Let’s add some CSS to style things.

In our `src` folder, create a new `css` folder and add a `style.css` file to it.

Inside our `style.css` file add:

body {

font-family: sans-serif;

max-width: 80ch;

margin: 0 auto;

padding-bottom: 24px;

}

h1 {

text-align: center;

font-size: 3rem;

}We now need to tell our `base.njk` to use our CSS file. Inside the `<head>` tag, at the bottom, add a link tag with our stylesheet.

...

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>{{ title }}</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/css/style.css" />

</head>

...We need to add a couple lines of code to our `eleventy.config.js` to get our stylesheet working. By default Eleventy is going to try to turn any files we have in our input directory into HTML. We don’t want it to mess with our CSS files, we just want it to use them as-is. So we’ll make a call to `addPassthroughCopy`.

We also want Eleventy to rebuild whenever we change our CSS file, so we’ll make a call to `addWatchTarget`.

We’ll add them both to the top of our config like so:

export default async function(eleventyConfig) {

eleventyConfig.addPassthroughCopy("./src/css");

eleventyConfig.addWatchTarget("./src/css/");

...

};Now you should see our styles applied to our journal, and things should be a little easier to read.

Displaying Entries on the Homepage

My original idea was to have a big calendar that displayed all of the entries, and you could click dates on the calendar to read the entry associated with that day.

To do that we’ll need to create custom filters, custom collections, and write some CSS to help create our calendar.

Let’s get started by creating a custom collection of our journal entries. In our `eleventy.config.js` let’s call the `addCollection` function to create a new collection called `journalEntriesGrouped`.

export default async function(eleventyConfig) {

...

eleventyConfig.addCollection("journalEntriesGrouped", (collection) => {

return collection.getFilteredByTag("entries").reduce((acc, entry) => {

const entryYear = entry.date.getUTCFullYear();

const entryMonth = (entry.date.getUTCMonth() + 1).toString().padStart(2, '0');

const entryDay = entry.date.getUTCDate().toString().padStart(2, '0');

return {

...acc,

[entryYear]: {

...acc[entryYear],

[entryMonth]: {

...(acc?.[entryYear]?.[entryMonth] || []),

[entryDay]: {

...(acc?.[entryYear]?.[entryMonth]?.[entryDay] || []),

entry

}

}

}

};

}, {});

});

...

};There’s kind of a lot going on here, but this will take all of our pages with the tag `entries` and get the `date` front matter we’ve added to them, then sort them into an object that is nested like our folder structure, grouping entries by year, month, and day.

We’ll also want to add a shortcode called `generateDays`. This will make more sense once we see the layout file, but this shortcode generates all of the days that will show on our calendar. If there’s an entry associated with the day, then we link to it. We also set a `–start-column` CSS variable that will be used to place what “Day” column of our calendar we put the first day of the month in.

export default async function(eleventyConfig) {

...

eleventyConfig.addShortcode("generateDays", function(year, month, monthEntry) {

const numberOfDays = new Date(year, month, 0).getDate();

let daysHTML = '';

for(let i = 0; i < numberOfDays; i++) {

let dayOfMonth = (i + 1).toString().padStart(2, '0');

let firstDayOfTheMonth = new Date(year + "-" + month + "-01").getDay() + 2;

if(Object.keys(monthEntry).includes(dayOfMonth)) {

daysHTML += `<li class="${i === 0 ? 'first-day' : ''}" style="${i === 0 ? '--start-column: ' + firstDayOfTheMonth % 8 + ';' : ''}"><a href="${monthEntry[dayOfMonth].entry.url }">${dayOfMonth}</a></li>`;

} else {

daysHTML += `<li class="${i === 0 ? 'first-day' : ''}" style="${i === 0 ? '--start-column: ' + firstDayOfTheMonth % 8 + ';' : ''}">${dayOfMonth}</li>`;

}

}

return daysHTML;

});

...

};Now that we have our group journal entries and shortcode, let’s create a custom layout to render them out and display it on our home page.

In our `_includes` folder, create another layout called `entrylist.njk` and paste the following:

<ul>

{% for year, yearEntry in collections.journalEntriesGrouped | dictsort %}

<ul>

{% for month, monthEntry in yearEntry | dictsort %}

<div class="calendar-wrapper">

<h2 class="month">{{ month }} {{ year }}</h2>

<ol class="calendar">

<li class="day-name">Sun</li>

<li class="day-name">Mon</li>

<li class="day-name">Tue</li>

<li class="day-name">Wed</li>

<li class="day-name">Thu</li>

<li class="day-name">Fri</li>

<li class="day-name">Sat</li>

{% generateDays year, month, monthEntry %}

</ol>

</div>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% endfor %}

</ul>Lots of looping going on here, but our `journalEntriesGrouped` collection is made of a lot of a lot of nested objects that we need to output.

We call the `dictsort` filter on our `collections.journalEntriesGrouped` to sort our years in chronological order. Because object keys can technically be in any order, this is just a nice assurance to get everything in line.

We then split our `journalEntriesGrouped` object into two variables, the object’s key will be `year` and its value will be `yearEntry`.

Then we do another loop, we sort our `yearEntry`’s keys and then split it into `month` and `monthEntry`. We display the month and year over top of a calendar, then start rendering the calendar.

We create our calendar wrapper, then hardcode our row of day names at the top of the calendar since they’ll never change. Then we take our `year`, `month`, and `monthEntry` variables and pass them into our `generateDays` shortcode to generate our days of the month.

And what we get is…very ugly. If you squint you can sort of see how it’s going to turn into a calendar. You can also see on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th how we have links which we can click to see our journal entries.

Styling the Calendar

Let’s add some CSS to make the calendar look more like a calendar!

In our layout we’ve already added CSS classes to our HTML, so we’ll have everything we need to select in our CSS. At the bottom of our `style.css` file add:

/** Calendar Styles **/

.month {

text-align: center;

font-size: 2rem;

}

.calendar {

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(7, 1fr);

place-items: center;

gap: 1px;

border: 1px solid;

background: black;

list-style: none;

text-align: center;

}

.first-day {

--start-column: 1;

grid-column-start: var(--start-column)

}

ol, ul {

padding: 0;

list-style-type: none;

}

.calendar li {

display: flex;

justify-content: center;

align-items: center;

width: 100%;

aspect-ratio: 1;

outline: 1px solid black;

background: #ddd;

color: black;

}

.calendar li a {

display: flex;

justify-content: center;

align-items: center;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

color: white;

background: maroon;

text-decoration: none;

}Now it’s looking like a calendar! And the days that have associated journal entries are showing up in red.

I don’t like how the month is a number, though. Let’s create our own custom filter to change that.

Back in our `eleventy.config.js` let’s add the following:

export default async function(eleventyConfig) {

...

eleventyConfig.addFilter("monthNumberToString", function monthNumberToString(intMonth) {

return Intl.DateTimeFormat('en', { month: 'long' }).format(new Date(intMonth));

})

...

};Then back in `entrylist.njk` we’ll use it on our `month` variable:

<h2 class="month">{{ month | monthNumberToString }} {{ year }}</h2>Looking better!

Navigating Between Entries

Clicking on a journal entry, reading it, going back in the browser, then clicking on another one is kind of a pain. Let’s add links at the bottom of the journal entry pages that allow you to go to the previous and next entries if they exist.

In our `journal.njk` file, we’ll create `previousEntry` and `nextEntry` variables in our template using some built-in filters that Eleventy provides to get the previous and next entries in a collection. Then we’ll put them at the bottom of our page and if there are previous or next entries, we’ll link to them:

---

layout: base.njk

---

{% set previousEntry = collections.entries | getPreviousCollectionItem %}

{% set nextEntry = collections.entries | getNextCollectionItem %}

<article>{{ content | safe }}</article>

<section class="entry-navigation">

<span>

{% if previousEntry %}<a href="{{ previousEntry.url }}">{{previousEntry.data.title}}</a>{% endif %}

</span>

<span>

{% if nextEntry %}<a href="{{ nextEntry.url }}">{{nextEntry.data.title}}</a>{% endif %}

</span>

</section>Let’s add some CSS to our `style.css` file, right above our calendar styles, to style this new section:

.entry-navigation {

display: flex;

justify-content: space-between;

}

/** Calendar Styles **/

...

Now we should see previous entry links on the left, and next entry links on the right.

Tag Time

I’m out of time on this blog post so I’m just going to spit out some code you can copy and paste to get tags set up.

In your `src` folder you’ll want to create a new file called `tag.njk` and paste this:

---

pagination:

data: collections

size: 1

alias: tag

filter:

- all

- post

- posts

- tagList

addAllPagesToCollections: true

layout: base.njk

eleventyComputed:

title: Tagged "{{ tag }}"

permalink: /tags/{{ tag | slugify }}/

---

{% set entrylist = collections[tag] %}

<ul>

{% for entry in entrylist | reverse %}

<li><a href="{{ entry.url }}">{{ entry.data.title }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

<p>See <a href="/tags/" all tags</a>.</p>And another file called `tags.njk`

---

permalink: /tags/

layout: base.njk

---

<h1>Tags</h1>

<ul>

{% for tag in collections.all | getAllTags | filterTagList %}

{% set tagUrl %}/tags/{{ tag | slugify }}/{% endset %}

<li><a href="{{ tagUrl }}">{{ tag }}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>Then add these two new filters to your `eleventy.config.js`:

eleventyConfig.addFilter("getAllTags", collection => {

let tagSet = new Set();

for(let item of collection) {

(item.data.tags || []).forEach(tag => tagSet.add(tag));

}

return Array.from(tagSet);

})

eleventyConfig.addFilter("filterTagList", function filterTagList(tags) {

return (tags || []).filter(tag => ["all", "entries"].indexOf(tag) === -1);

})In `journal.njk` you’ll want to add your tags template code between your `<article>` and `<section>`:

{% if tags | filterTagList | length %}

<section>

<p>Tagged with:</p>

<ul>

{% for tag in tags | filterTagList %}

{% set tagUrl %}/tags/{{ tag | slugify }}/{% endset %}

<li><a href="{{ tagUrl }}">{{tag}}</a></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

</section>

{% endif %}And you’ll be able to see your tags at the bottom of your entries, click on them to see other entries that share the same tag, and see a list of all tags used in your entries.

Make It Your Own

This is just the start! Use this as a template to make your own styling tweaks and new features. Maybe you want to add some front matter where you can list your mood, or how the weather was that day. You have the know-how on how to do that!

And hopefully building this gives you the momentum to start journaling. In a few years you’ll have plenty of memories to look back on.

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.