The Rise of Train Robberies

In the 1890s, train robbery was a major problem in the United States. Most passenger trains included a locked and guarded express car, which was used to transport cash between banks and businesses throughout the country. Train robbers worked in teams. While watchmen guarded the outside of the train, and two or more men robbed passengers of cash and jewels, one team broke into the express car, subdued the guard, blew the safe open, and hauled off enormous amounts of cash.

The Public’s Sympathetic View

Train robberies were a favorite subject of the American press, and many readers secretly or openly sympathized with the daring outlaws whom they saw as modern-day Robin Hoods. By the mid-1890s, the country was more than two decades into a period of tumultuous social and economic change. Large-scale industry was destroying family businesses, upending communities, and supplanting the traditional agrarian way of life.

As millions of people worked long hours in grueling industrial jobs for low pay, they watched the railways, banks, and industrial cartels go unpunished as they amassed wealth and power through collusion, bullying, price-fixing, and blacklisting. If Robin Hood now and then took his revenge against these invulnerable giants, a substantial part of the public wasn’t going to shed a tear.

The Burlington Line Incident

Sick of being robbed, however, the railroads decided to fight back. When a police informer named N.A. Hurst tipped them off about a plan to hold up the Burlington line’s Number 3 train, the railroads saw their opportunity. The hold-up was to take place on the night of Sunday, September 24th at Roy’s Branch, Missouri, just north of St. Joseph. Hurst, the informer, had embedded himself in the gang of would-be robbers, and kept the police and railroad officials apprised of their every move.

To thwart the plan, Burlington assembled a dummy train to look just like the Number 3, and then loaded the express car and the passenger cars with armed law enforcement agents instead of regular passengers. They drove the train to Roy’s Branch, stopped at the robbers’ signal, and then began a shootout pitting fourteen armed lawmen against three robbers.

One of the three ran off after being shot in the hand. The other two, Hugo Gleitze and Fred Kohler, were killed and then loaded onto the train and hauled back to the Francis Street Station in St. Joseph, where railway operators put the corpses on display like hunting trophies. The point was to show the public and the press that the railroads were getting tough on crime.

This public relations stunt backfired spectacularly. The townspeople on the platform know that Kohler was no hardened criminal. He was eighteen years old, newly married, and had never been in trouble before. Gleitze, in his early twenties, was the child of a widow who happened to be in the station when the train returned, and the crowd reacted strongly to her cries of grief. The citizens soon learned that the railroad had known of the planned robbery for weeks and had not tried to stop it. The story became headline news across the country, and most readers saw Kohler and Gleitze as victims of entrapment and murder.

Pat Crowe’s Notorious Career

Among those angered by the incident was Pat Crowe, a seasoned bank and train robber known for his iron nerve and his ability to avoid capture. Crowe showed his contempt for Burlington’s PR stunt by successfully carrying out the same robbery that Kohler had planned, in the same place, against the same train, just a few nights later. Many readers saw this as an act of retribution against a rich corporation that had murdered with impunity.

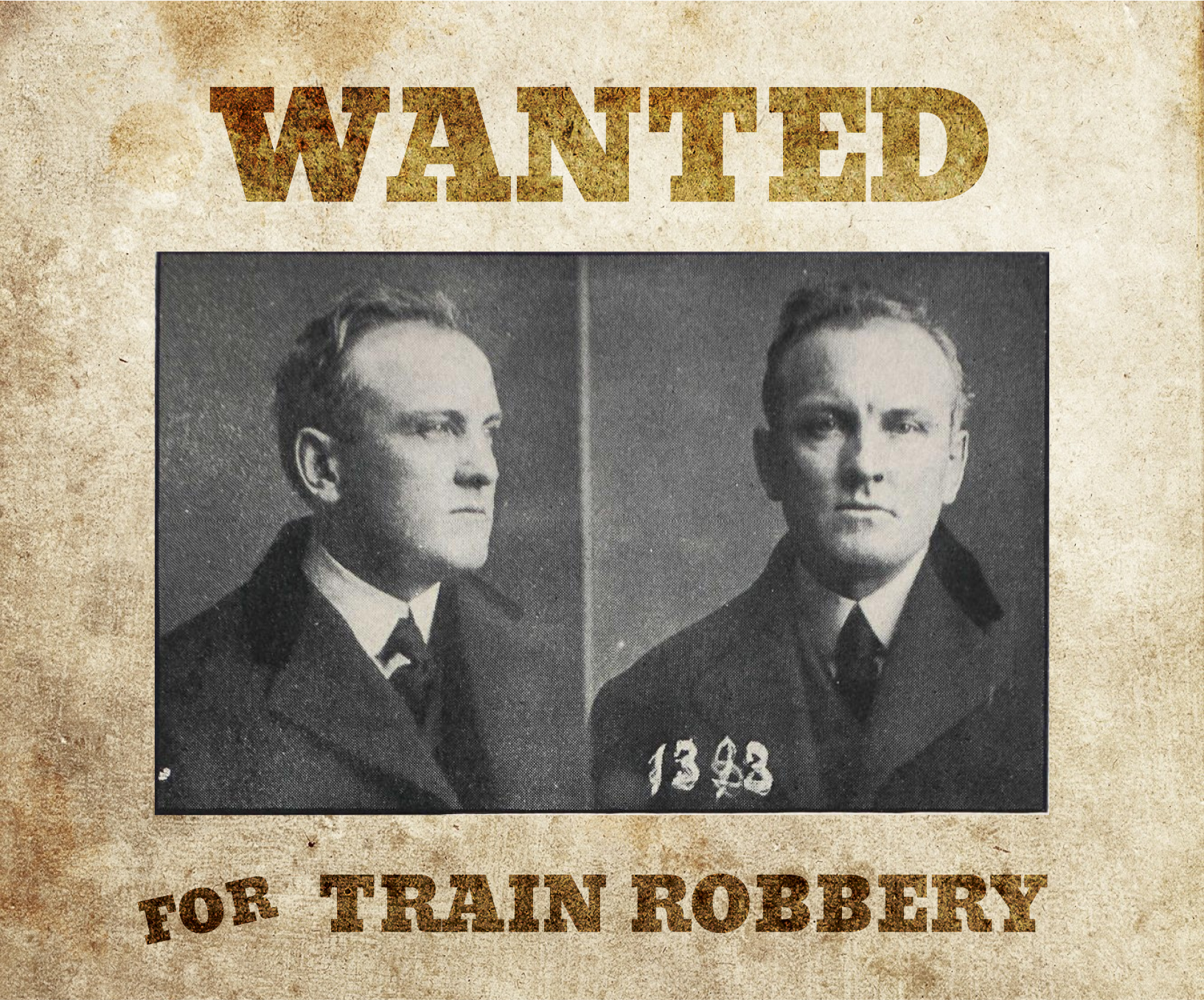

Before his career was over, Crowe would be wanted for bank robbery in Ohio and West Virginia, and for a series of train robberies in Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. He would break jail in Iowa and Missouri, and use political connections to win release from the maximum security prison in Joliet, Illinois. He escaped lynch mobs in Chicago, Kansas, and Iowa, and walked away unscathed from an assassination attempt in Omaha, a four-on-one ambush ordered by the chief of police that unfolded before a crowd of witnesses.

Crowe’s brazen crimes and colorful escapes made him a staple of daily newspapers throughout the country. In those days before the existence of federal law enforcement agencies, governors throughout the US turned to the Pinkerton Detective Agency to pursue Crowe across state lines. Despite the fact that Pinkerton employed more detectives than the US Army had soldiers, they still couldn’t catch him. Eventually, William Pinkerton himself took over the case. Crowe publicly humiliated the famous detective, leaving him a bottle of champagne and a sarcastic letter of apology after escaping the jail cell in which Pinkerton had left him.

The Cudahy Kidnapping

Crowe’s most infamous crime was the 1900 kidnapping of Edward Cudahy, Jr., son of the millionaire meat packer who had put Crowe’s neighborhood butcher shop out of business ten years earlier. After undercutting Crowe on prices and driving him into bankruptcy, Cudahy Sr. hired him into a low-wage cashier position and then fired him for allegedly stealing twenty dollars from the till.

In this period of rapid industrialization, many Americans understood the bitterness of losing the freedom and autonomy of self-employment and then having to submit to an entry-level position in the company that had destroyed their livelihood.

After kidnapping Cudahy Jr., Crowe demanded a ransom of $25,000 in gold coin, and he got it. For the next five years, he avoided the largest manhunt in US history, a search that encompassed nearly every state as well as the United Kingdom and South Africa. For years after his disappearance, supposed sightings of Crowe continued to make headlines throughout the country, even though the man himself was nowhere to be found.

The Trial and Public Sentiment

In 1905, tired of living on the run, he turned himself in to be tried for the kidnapping in Omaha. By this time, American sentiment against the abuses of wealthy corporations was reaching a peak. President Theodore Roosevelt had made trust-busting the centerpiece of his domestic agenda and had recently won reelection with broad public support. When his train arrived at the Omaha station just before Crowe’s, five thousand supporters turned out to greet the nation’s leader. Later, twenty thousand turned out to meet Crowe.

They found him to be the man that journalists, policemen, and jailers had come to like in spite of themselves. Handsome, intelligent, confident, and articulate, Crowe connected easily with people from every level of society. He counted among his friends the remnants of Jesse James’ gang, several US senators and presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. (For years, Crowe’s adventures had helped drive sales of Bryan’s newspaper, the Omaha World-Herald.)

As Crowe’s trial approached, people remembered it was Cudahy who had put him out of business in the first place. They remembered Crowe as the one who retaliated against the powerful railroads when the law wouldn’t hold them to account. And they remembered how he had mocked and humiliated William Pinkerton, whose detective agency was becoming reviled as the attack dog of the robber-barons, hired to brutalize and intimidate striking factory workers.

Despite overwhelming evidence against him, and despite the fact that he offered no testimony and no defense, Crowe was acquitted by a jury that felt intense antipathy toward the wealthy industrialists Crowe had targeted. The only time Crowe spoke at the trial was during the testimony of the victim, Edward Cudahy, Jr.

When asked if he had smoked during the days when Crowe held him captive, Cudahy Jr. glanced nervously from the witness stand to his father, who disapproved of tobacco, and said, “No.” In front of a packed courtroom, Crowe leapt from his seat and said, “What? You smoked the whole time!”

If that didn’t incriminate the man, what would?

The Cudahy case became the first successful kidnapping in American history, success meaning that the kidnapper got to keep the ransom without ever being punished. While the judge and many in the press lamented Crowe’s acquittal as one of the worst miscarriages of justice in American history, it did have a beneficial side effect. In 1900, many states, including Nebraska, where Crowe had committed his crime, had no law against kidnapping. The crime was so rare, it simply hadn’t occurred to legislators to ban it. After the Cudahy case, all states had explicit laws against kidnapping.

Crowe lived in an era much like our own, in which rapid technological change and industrial consolidation disrupted the traditional economy, creating huge economic disparities between corporations who were creating the new order and individuals who struggled to adapt. In Crowe’s day, industrialization and mechanization were the disruptors. In ours, the Internet, technology and AI have changed the economic fortunes of millions.

Then, as now, rapid transformation polarized American society. Like many of today’s public figures, Crowe inadvertently became a lightning rod of public opinion. People either loved him as a knight of the old order or hated him as a thief.

Eventually, government policy was able to adapt to the technological and economic changes, curbing the excesses of the new corporate titans, smoothing out the worst of the economic disparities, and defusing many of the tensions that had polarized the country.

Pat Crowe’s Later Years

After the Cudahy trial, Crowe retired permanently from his outlaw life. He spent his last thirty-four years preaching against crime and advising the US government on prison reform. By the end, the one-time bank robber had come full circle, working for a while as a bank guard in Washington, DC, happy at last to put all the turmoil behind him and live a quiet life out of the public eye.

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.