This past year I took a new side hustle. The job? Sixth grade math tutor of my 11 year old son. Every day at work I use PEMDAS, statistics, basic algebra, percentages, and ratios … so why was this familiar topic so hard to explain? I was very demoralized initially. It paralleled one of the great paradoxes in building digital products.

The Curse of Knowledge

Subject matter experts deeply know the problems and are passionate in the solving of them, but struggle to convey fundamental principles, constraints, procedures, and solutions to their intended audience.

We have all seen this same pattern repeated many times in life and work. It is difficult for an expert to unpack all their knowledge for a novice. Recently, an accomplished domain expert confessed their own backward approach to me. “My instinct is that if someone doesn’t get what I’m trying to explain, I am tempted to flood them with more and more details.”

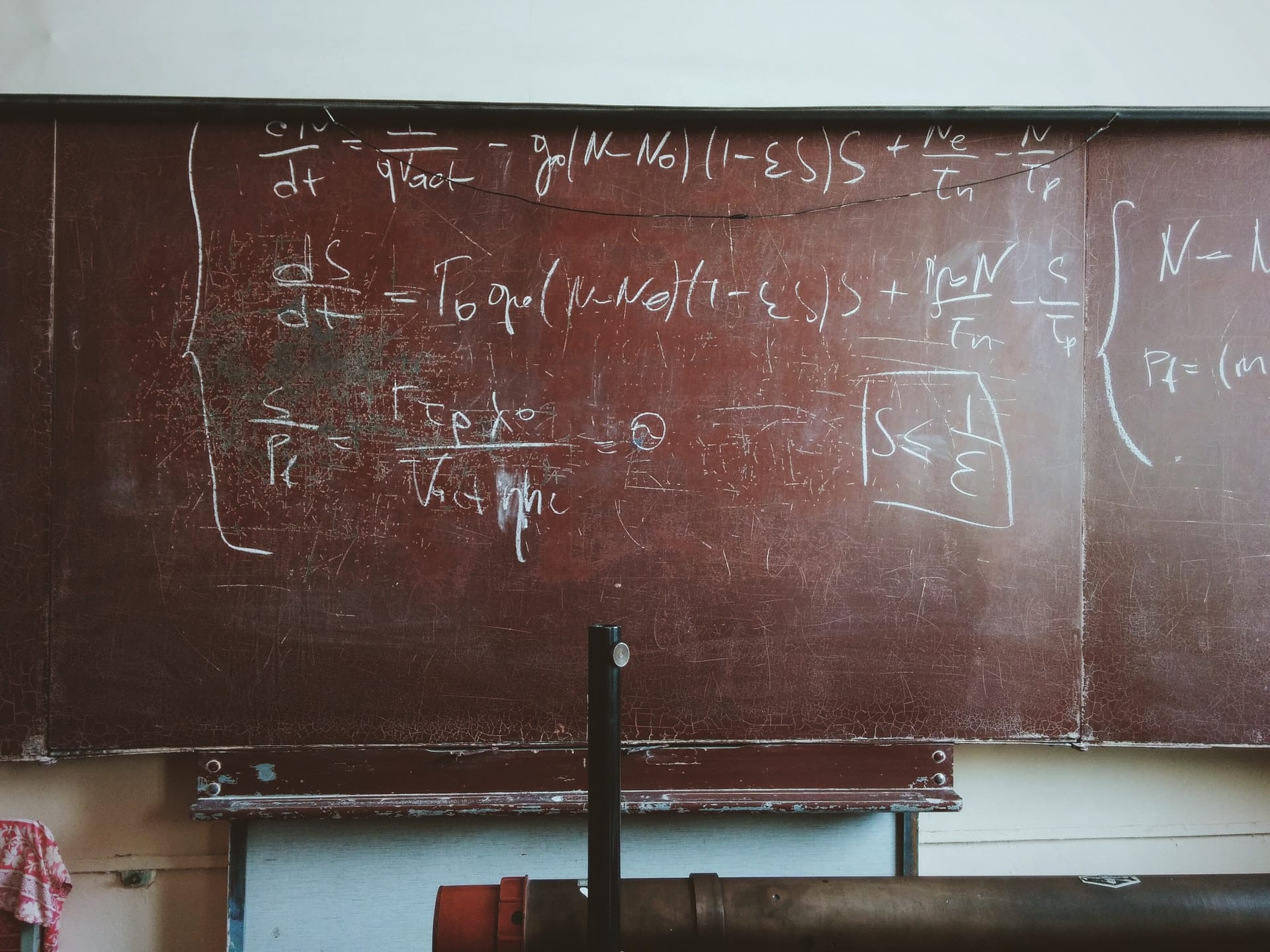

Less can be more — as long as it still represents a holistic treatment of the subject or problem. Richard Feynman was one of the greatest physicists of the last century. In the book Feynman’s Lost Lecture, David and Judith Goodstein wrote about Feynman’s self-testing framework which he called the “Freshman Lecture” to gauge his own understanding of an abstract subject:

Feynman was a truly great teacher. He prided himself on being able to devise ways to explain even the most profound ideas to beginning students. Once, I said to him, “Dick, explain to me, so that I can understand it, why spin one-half particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics.” Sizing up his audience perfectly, Feynman said, “I’ll prepare a freshman lecture on it.”

“But he came back a few days later to say, “I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t reduce it to the freshman level. That means we don’t really understand it.”

If Nobel Laureates who pride themselves on their ability to break down complex topics can’t always do it, then how do we as product teams break out of this paradox?

Getting back to my tutoring job, my approach was lacking. I didn’t prepare. I never distilled. I couldn’t atomize concepts in order to build them back up. I had a lack of empathy for my son’s level of context. Despite my knowledge of the subject matter, at the start I was unable to explain what amounts to everyday computations for most adults because I hadn’t spent sufficient time at the start assessing his learning, thinking about the goals, and setting a basic approach on how to get there.

Building Products

So how does this apply to building digital products? For any subject matter expert or product owner — whether they became so accidentally or intentionally — I would encourage you to learn from my tutoring job.

Instead, work from first principles. According to Goodstein’s book, Feynman once proved the 500 year old laws of elliptical planetary motion using the 2,200 year old tools of Euclid. This work is hard but can be fundamental when it comes time for assembly; be it the assembly of a software product, or the minds of budding young theoretical physicists, or an 11 year old grokking algebraic equations.

Think about the problem you are solving. Break it down to fundamentals.

Only then will those thought exercises lead to efficiency in explaining the need, building consensus, and evangelizing whatever amazing product you ultimately build.

What I cannot create, I do not understand.

— Richard Feynman, Theoretical Physicist

Loved the article? Hated it? Didn’t even read it?

We’d love to hear from you.